Toru Dutt (1856-1877), a 19th century Bengali woman writing exclusively in English and French, is best known as one of the first Indian women to respond intellectually and creatively to the literary and cultural ideologies of the West. The fact that she wrote at all, and that too in English, was due to the stirring processes of change that formed the central motive of 19th century Bengal. Western education through the medium of English, originally a political necessity for maintaining the Empire, soon became, for Indians, a tool to gain access to the ideas of modernity and progress that the post-Enlightenment West came to symbolise. For Toru Dutt, her family’s conversion to Christianity six years after her birth necessitated a further moving away from traditional orthodoxy, symbolised by Hinduism, into Westernised and, by association liberalised currents of thought. Toru’s deliberately anglicised upbringing and the efforts on the part of her father to educate his children in the literature and languages of Europe completed this process. At the time of her demise at the age of twenty-one, Toru had published a collection of French verse translated into English (A Sheaf Gleamed in French Fields) and had been working on a collection of English verse based on Sanskrit legends (Ancient Ballads and Legends of Hindustan). She was also working on a French novel and an unfinished draft of an English one- all of which was published after her death.

Anthologies on Indian writing in English categorise Toru Dutt as one of the ‘pioneers’ alongside Kasiprasad Ghose, Derozio and Michael Madhusudan Dutt. Over the years evaluations of Toru have been as diverse as her achievements. Edmund Gosse called her “This fragile exotic blossom of song” which established the standard critical response to her in the 19th and early 20th centuries as a literary curiosity.

Indian criticism was more uncomfortable. In a volume entitled Great Women of India, The Holy Mother Birth Centenary Memorial the editors concluded that “India hugs her to her bosom, no doubt, but finds nothing to show as hers, India’s”. More recent evaluations show Toru as a bridge between divided cultures, reconciling in art the spiritual exile of real life. Our Casuarina Tree – one of the seven poems on personal topics that ended the Ancient Ballads volume is one example of this complexity where she keeps her roles as Bengali/ India/ Christian/ exile in a fine balance.

The central symbol of the poem is the Casuarina tree. The poem follows a careful pattern of actual description (Stanzas 1 and 2) into an evocation of the tree as a symbol of childhood memories and associations (Stanzas 3 and 4). The first stanza describes the trunk of a giant tree encircled by a creeper of red flowers, providing day and night a haven for birds and bees. The second stanza continues the description and shows the tree at break of day, at noon and at twilight. In the third stanza there is a change in tone whence the tree metamorphoses into a symbolic link between the loneliness of the present and a joyous past. The sweet companions are Toru’s siblings no more – Abju who died in 1865 and Aru who died in 1874. The wind sighing through the casuarina tree blends with the melancholy murmur of waves breaking on the shore of the foreign lands Toru is now in. The picture dissolves into the poignant overtones of a traveller in foreign land, pining in a painful moment of nostalgia, for the comfortable familiarity of “one’s own loved native clime”.

One of the key features of this poem is of the sense of a writer caught between two worlds. Toru uses the English poetic model and its accompanying inheritance of stock metaphors, idioms and techniques. There is also the own world of the writer which was completely Indian. Hence the two worlds exist side by side-and the choice of the Casuarina tree, images like the python, kokilas, the grey baboon, the broad tank and the water lilies exist alongside highly stylized poetic language reminiscent of the great Romantics. The poem ends with a reference to a poem by Wordsworth, thereby acknowledging the world of the West and the literature of England as source and poetic inspiration.

Our Casuarina Tree exists as a poem of assimilation, one where English Romanticism is not just a flavour but where Indian and Western idioms coalesce in an organic whole. The technique is of the classic Romantic ode with its carefully crafted argument spread over five sections. The overall feel is of a deeply felt personal experience. There is a sense of loss, pain and suffering seen through the recurring image of the rolling seas. The joys of childhood are a contrast to the loneliness of the present. There is also the sense of a vast gulf, not only between the tree and her present surroundings but also between the two worlds that Toru lived in. Paradoxically she belonged to neither.

Writing at a time when Indian women were tentatively spreading their wings, Toru takes this self-fashioning a step further by producing a poem that relocated her western learning with her Indian identity. The poem is a testimony to the in -between characteristic of Toru’s own life – Indian yet Westernised, imitative yet still original, restless voyager yet yearning for her motherland, hemmed in by her contemporary constraints yet still breaking free of them. The poem shows an adaptibility that has ensured that it has survived and is significant today in a way that many other poems of her time are not.

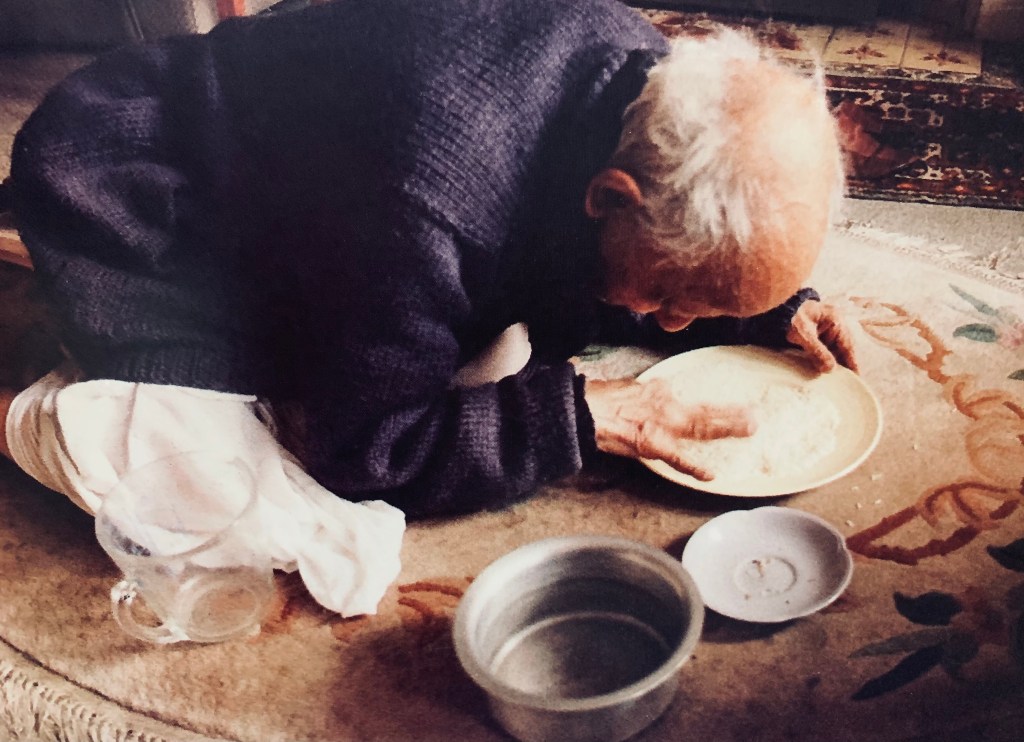

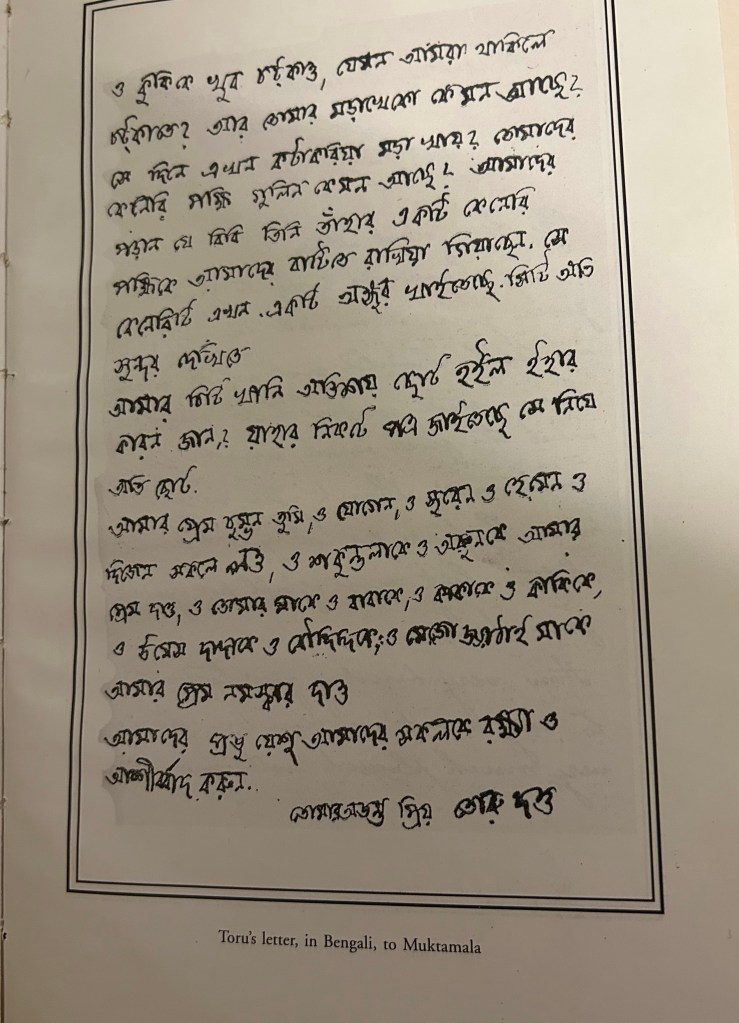

The only extant letter in Bengali by Toru Dutt, found in Harihar Das’ biography and reproduced above is written in a stilted halted language. The photograph of the Baugmaree garden house in what was then a suburb, where she spent her happiest days, free from the travails of the large joint family in the lanes of North Calcutta is also found in the same book. Toru’s grave lies near Maniktala Street, along with that of her family and has been preserved after many years of terrible neglect. Although she had hoped to return to England as a place of freedom and creativity, her illness prevented her from making the move. In her last letters written to her friend Mary Martin she had acknowledged her in-between status by melancholy acceptance- it was sad to leave her own land and begin a life elsewhere. Toru Dutt languished in school text books for many years before making her way in to the world of serious scholarship. This poem encapsulates all that she longed for, received and accepted.

May love defend her from oblivion’s curse.