Before the 19th century, Englishmen taking their first faltering steps in India were fed on local food. A young factor at Surat in the 17th century wrote of “Cabob…not unlike a ghoulash, that is chicken boiled in butter and stuffed with raisins and almonds, with mango achar“. English food itself had not matured from its medieval tone, and the Indian roast was similar in many ways to the English pie and associated spices like cinnamon and caraway. The factors of the East India Company sat in a strictly hierarchical manner, were served on heavy cups and platters of silverware and consumed copious amounts of drink. Arrack, distilled in South India from fermented palm juice, or wine from Bengal, made from fermented rice, made the rigours of India tolerable to the young men. Meals often ended in carousal, song, dance and finally the oblivion of the very drunk.

As Company influence grew, more and more Englishmen came out to India to make money, leaving their families behind. Between soldiering, administering, trading and simply being there, life began to resemble the jaunt of a Freshman who has just flown the nest.

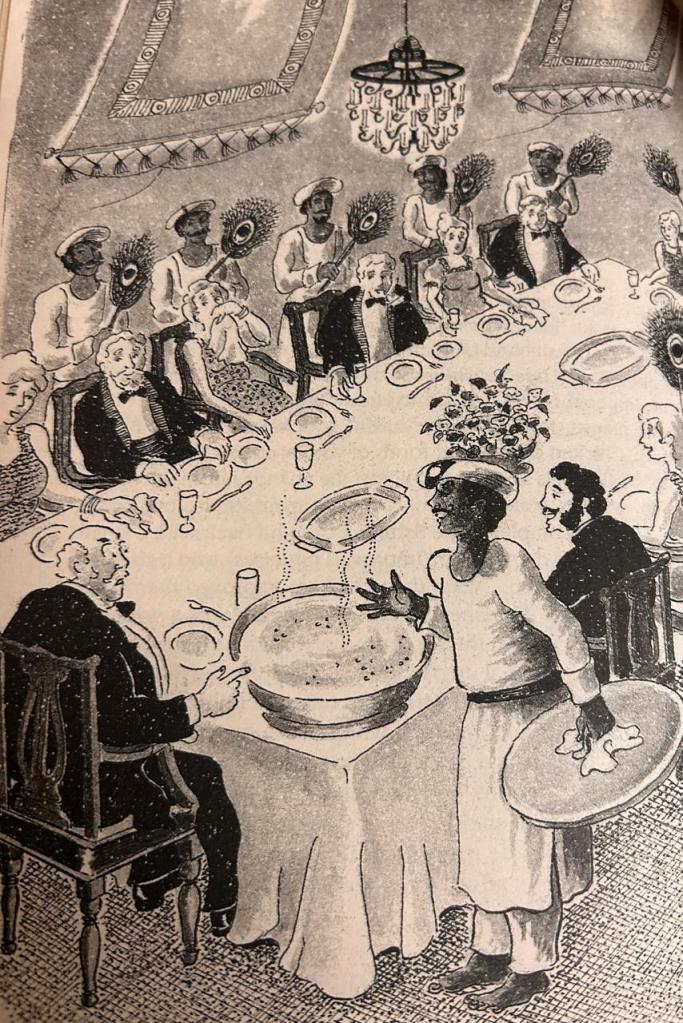

As time passed, Empire grew and with it the British preoccupation with eating and drinking. There was an obsession with lavish breakfasts, luncheons, teas and dinners, with burrakhanas and elaborate feasts. The pagoda tree shed money and this newly found wealth displayed itself in food and drink.

As the import of spirits from Europe increased from the eighteenth century onwards, so did the drinking. Now there was a lot more to choose from and in came champagne, claret, Madeira, port and beer. Claret was favoured; it was called loll shraub and was considered good for indigestion. Gin and tonic was hoped to ward off malaria because of the quinine in tonic water. Pale beer, brewed for the Indian market, was considered neccesary for the heat. The first brewery was set up in Solan district in 1830 and by the 1880s there were twelve breweries in India. With better communication lines, foods imported from England became de rigeur and fresh salmon, cod, oysters and caviare joined the Anglo-Indian table.

Calcutta , the capital of Empire, was filled with taverns, boarding houses, coffee houses and hotels. In 1835, a young cadet arriving in Calcutta recounts the glories of Spences Hotel: “Picture to yourself a snow-white tablecloth on which was drawn up in beautiful array, ham, eggs (fresh for a change), a superb kind of fish from the salt-water lake, called a becktee or cokup fried, boiled rice, muffins, tea, coffee etc. plantains, radishes, small pats of butter in a handsome cut glass vessel of cold water, and a bouquet of flowers in the centre gave a most cool and refreshing appearance to the table...”

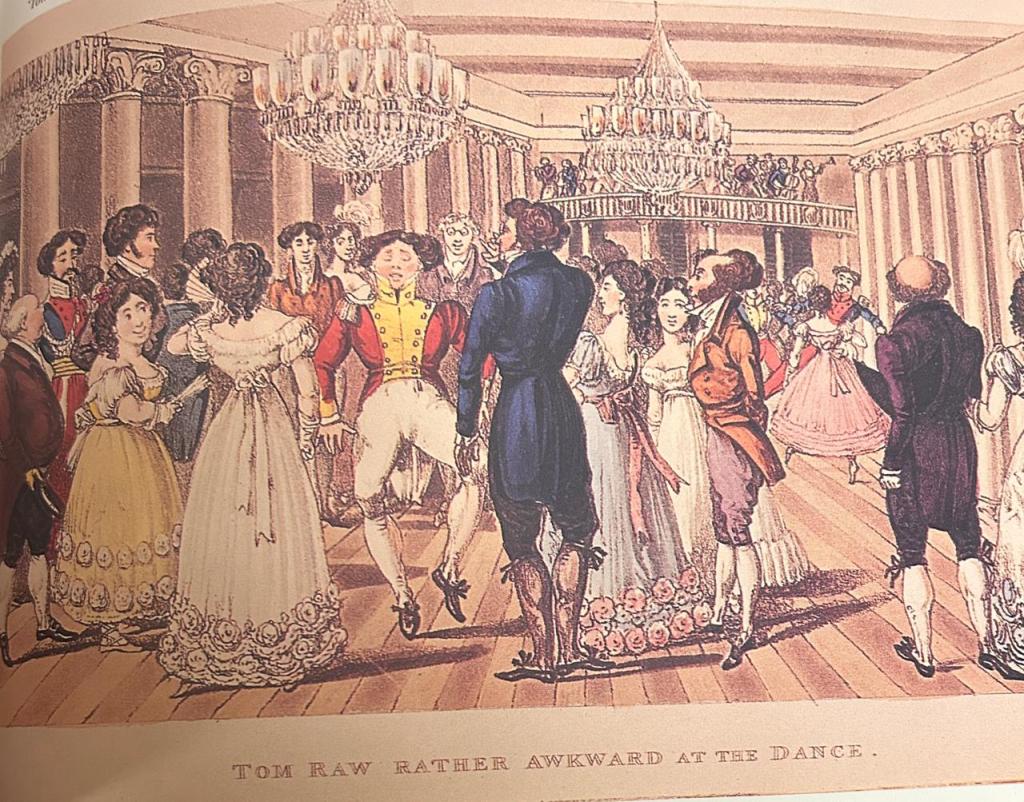

At Government House, Calcutta and the one at Barrackpore, Emily Eden, sister of Lord Auckland describes how the enormous breakfasts had to be followed by equally gargantuan luncheons. “The breakfasts in India are excellent-fish, curries, omelettes, preserves, fruits etc”. Tom Raw, the griffin immortalised by D’Oyly , on one of his very first meals in India describes how “the conversation, like all table talk,

Turned on the daintiness of sav’ry dishes,

On the fat beef and delicate white pork,

The firmness wonderful of cockub fishes,

And tarts and puddings cooked up to one’s wishes.

With -“Let me help you, sir, to this great ragout,”

“Did you say loll shraub?,-“Lord, sir, you’re facetious

I have the honour to-“Some of that stew,

I like this giblet curry-Pray ma’am, what say you?”

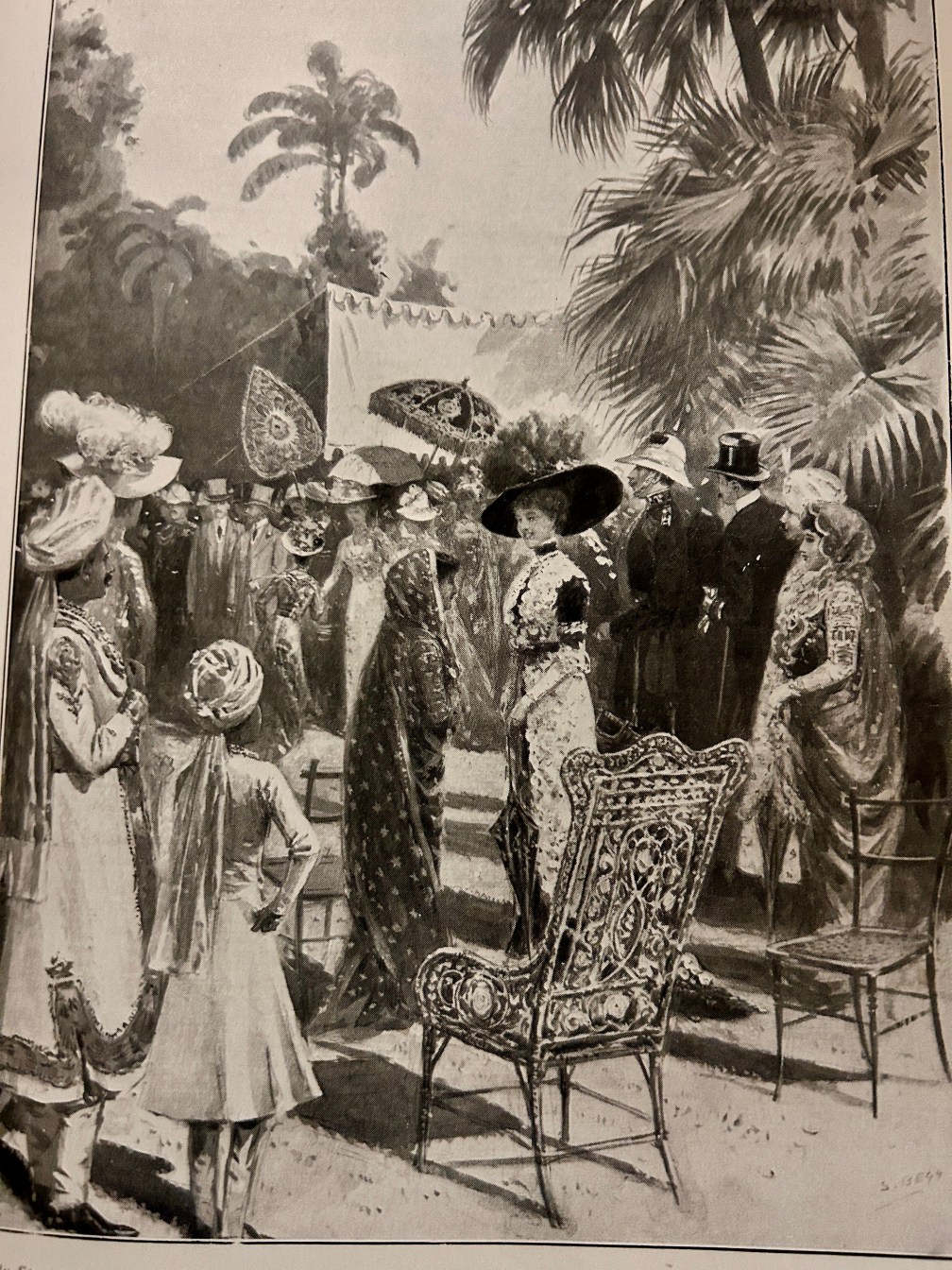

After 1858, the era of the boisterous nabob, wining and dining with Indian chiefs was replaced by a haughty withdrawal from all things ‘native’ and a desire to replicate the pleasures of home. Englishwomen had also begun to come out to India to marry and set their husbands in strict modes of discipline, the bachelor headiness of the 17th century gave way to a more structured routine. The women had staked their all on their marriages, driven to India on ships to escape eternal drudgery and spinsterhood at home, known simply as “the fishing fleet”. This was a fairly large number of daring young women who braved the hazards of the climate and the strangeness of the people to become the ‘memsahib’. Their first outing was to recover their looks and then wait for invitations. “…everybody with the look and attendance of a gentleman is at liberty to make his appearance. The speculative ladies, who have come out in the different ships, dress themselves with all the splendour they can assume, exhausting upon finery all the stock of money they have brought with them from Europe”. Only a few were left out of the marriage market; sex and the need to maintain racial superiority meant the fleet managed to hook all kinds of fish. The memsahib’s life would then begin.By 21st century standards a memsahib’s life was sadly limited. The husbands toiled during the day, with short breaks of tiffin, chota hazry and lots of drinks, but apart from the ritualistic attendance at the club, the memsahib had nothing much to do save eat, sleep and buy rolls of muslin. The missionary wives had dutiful roles to enact, like Bible studies and a spot of heathen welfare, but for the vast numbers of army wives, businessmen’s wives or those whose husbands were in the Civil Service-the archytypal memsahib, in fact, the most important ritual of any day was food.

The memsahib was expected to keep open house, throw parties and replicate the glories of hotels at her domestic table. She was helped by self help books- “The English Bride” by Chota Mem and the famed “The Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook” by Flora Annie Steel and Grace Gardiner are classics. With her inadequate knowledge of local languages and the local produce, she nevertheless nurtured visions of grand dinners, levees, and banquets. There was only one way out and that was to rely on the bobachee (bawarchi). Of all the servants this man was the hero, unsung but the nerve centre of the colonial home. Bobachees were usually Goans or Muslims for no Hindu would touch beef. The bobachee adapted English recipes, adding innovative Indian ingredients and magical touches till the aha moment came, and Anglo-Indian cuisine was born.

The cuisine that came in was a vast hybrid. Some dishes were deemed to be appropriate reminders of the lost tables of England while others had the bobachee’s cunning hand. Jellies and joints, soups and salads vied for space alongside an anglicised version of curry and rice. The mulligatawny soup, a vindaloo, a cutlet with chutney and the kedgeree were invented with inspiration and out of necessity. Meals became more and more complicated and a battleground for cultural clashes.

Curries were a must for at least one meal a day. The word itself was derived from the Tamil ‘kari ‘and the Kannada ‘karil,’ ‘to eat by biting’. Hobson Jobson described the true curry as an additional relish, “a dish of meat, fish, fruit or vegetables, cooked with a quantity of bruised spices and turmeric; and a little of this gives flavour to a large mess of rice”. Anglo-Indian dishes with a touch of curry powder became essentials. The ‘Country Captain’, a dry curry sometimes served for breakfast, was thought to have been favoured by skippers of country boats. Another dish was ‘Sudden Death”- a staple of dak bungalows where the bobachee, told to rustle up a dish for a sudden guest, caught, killed and grilled within an hour or two a one -month -old chicken for a hearty meal.

Curry became one of the most enduring legacies of Britain’s overseas rule. In colonial households it was made from leftover meat, spices added were hoped to enhance taste as well as nutrition. From the 19th century onwards commercial curry powders began to be made and in time the curry became a loaded word. From the 20th century onwards the word acquired subtle meaning, either as a word of insult, associated with spice-laden alien cookery or as a symbol of resistance. In 2023, an Indian PhD student in the USA was heating his palak paneer in the common microwave of his shared kitchen when he was asked to stop by another collegue who disliked the smell. Two years later the case concluded with damages of 200,000 dollars being awarded and both students barred from the University for life. As a lover of palak paneer one can only conclude the curry had mutated to a symbol of the Other. Much like palak paneer, the British in India, had an edgy relationship with Anglo-Indian food. Certain smells became politicised, and while it was all right to taste a savoury meat dish made by a bobachee from within the household, it was never deemed appropriate to taste more robust ‘native’ variations on fish and vegetables at official dinners.

The bobachee had to arm himself with various menus. At dawn was chota hazry, a light meal of tea, toast or fruits before the sahib and memsahib took a turn in the dewy coolness. As the heat became murderous, so did the activity in the kitchen. From what we read in the housekeeping books, hog heads were boiled, mutton was quartered, fish was de-boned and beef was stuffed with sauces. The chutney and the Worcestershire sauce was invented.

Soon came breakfast, with chops, fried fish, quail, steak and kedgeree. The kedgeree was a version of the khichri but was infinitely anglicised, with recipes calling for the rice to be mixed with hard boiled eggs, boiled fish, butter, milk, cayenne pepper, and sweet chutney. After breakfast there was rest under the cooling punkah before tiffin- a lighter meal, followed again by tea and cakes, rounded off at night by another grand dinner. But dinner, in keeping with the mood of racial segregation had to be a Europeanised version. It pretended to be free of all Oriental influences and adhered to the set pattern of ‘home’-canned fish, cheese, jam, dried fruit alongside bland joints of lamb, saddles of mutton and boiled chicken. Curries, mulligatawny and kedgeree could be consumed privately during the day, but the sense of racial segregation and superiority had to be kept up when entertaining at night.

Bobachees had their own versions of spellings and names that would often leave memsahibs racking their brains. Here is a latter day memsahib’s account of her cook’s bazaar book, almost like Finnegan’s Wake.

“Dead Furit, Dat Furit, Gerapes, Spinge, Duck Kill Gillen, Bhaket Fish.” Which is Dried fruit, Dates, Grapes, Spinach, cost of duck, plus killing and cleaning, Baked fish.

The memsahib and the bobachee had a complex relationship. They were bound to each other by the needs of creating dishes that, it was hoped, would become a form of art. But the bobachee was also a shrewd taskmaster, deftly improvising, refusing to give in to the memsahib’s curt commands and often pilfering.

Here is a memsahib’s account of life with a bobachee.

Cook also did the shopping and always took his perk: ‘If you tried to go down to the shop to do your own purchasing you were just asking for another twenty-five per cent more to be added to your bill. If your cook brought things for you he just put a little more on the list than he had paid, but that was his dastur.’ Dastur, as Kathleen Griffiths explains, was an immutable fact of Indian life: ‘You could leave your jewellery, your money, your bungalow wide open and nothing would ever be taken from it. Their devotion and honesty to you personally was absolutely amazing, but as regards their little perquisites in the way of food or making a little bit on the bazaar, all this was taken as part of their daily life and you accepted it. If I thought the cook was adding on a little too much I would say to him, “Oh, cook, I think you’ve made a little mistake; you’d better go into the cook-house and reckon it up again and then come back to me and tell me.” And he would come back and say, “Oh, yes, memsahib, I wrote five rupees instead of five annas.” ’

After 1947 the cult of the bobachee was on the wane. The British packed up and left and those amongst the Indians who had acquired Westernised ideals struggled with the task of keeping the old Anglo-Indian food habits alive. Much of it survives today in the British built clubs, the last bastion of Englishness. that do brisk business in the Continental section despite the Chinese room and the Tandoor Corner. At the Gymkhana in Delhi, or the United Services Club in Mumbai one may still have a selection of roasts and cutlets. The clubs in Calcutta (Kolkata?)offer a menu that must have been the handiwork of an intrepid bobachee many many years ago- Bekti Muniere, Saddle of Mutton, Gammon steak, Baba Au Rum, Poached pears in Port Wine. All along Park Street, Calcutta’s answer to Times Square, restaurants thrive on Prawn Cocktails and Asparagus Soup.

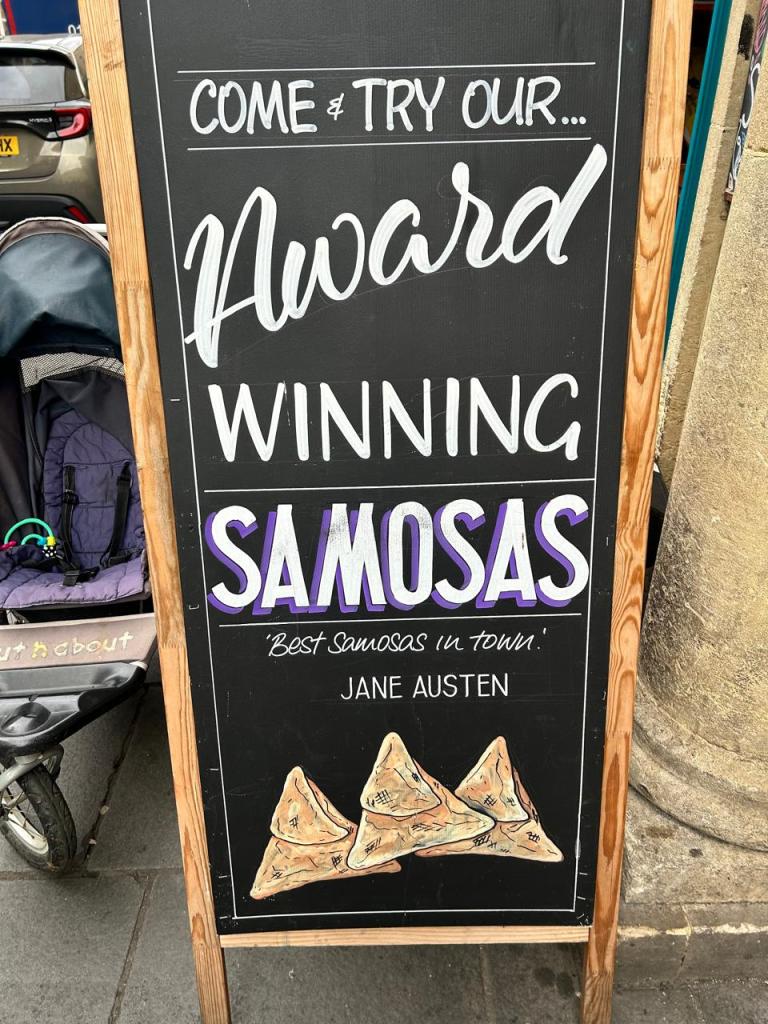

Meanwhile Indian takeaways abound in Great Britain. Kebabs, tikka masala, Himalayan Chicken and chutney with poppadums line any self-respecting English town. There are Austen samosas at Bath and jhal muri outside the British Musuem. Violently coloured red curries are served in a scattering of eating-rooms with suggestive names like Taj Mahal, The Lotus or Thali Food. Food boundaries have become blurred in the UK- a salad or a casserole may be an everyday quiet need, but for a special occasion, one suspects that the British turn, not to fish and chips but an outing at an Indian restaurant. The Empire cooked back and the bobachee-memsahib partnership, born out of necessity, endured beyond anything they could ever imagine. Here is a short poem that shows the dynamics of power.

You are fat, my khansamah,” the mistress said

You no longer do up your top button.

Small points, I agree, but perhaps they connect

With the fact that we use so much makkan”.

In my youth, said the cook, I worked for my baap

Who was certainly a very wise man.

He said that a cook must be skilled in the art

Of making whatever he can.

You are old, my khansamah, the mistress said

And your hisab is daily as long as my arm,

And you always extract the last pie.

If the hissab is long, the khansammah replied

With a smile that was meant to placate,

Will the memsahib please take her pencil and write,

Or tiffin for the sahib will be late”.

For those interested in reading more, do take a look at “A History of Food in India” by Colleen Taylor Sen, “Plain Tales from the Raj ” by Charles Allen and “Calcutta Through British Eyes” by Laura Sykes.

The images above are taken from the following sources:

The King and Queen in India, 1911-1912, Stanley Reed, Bennet Coleman and Co, Bombay 1912

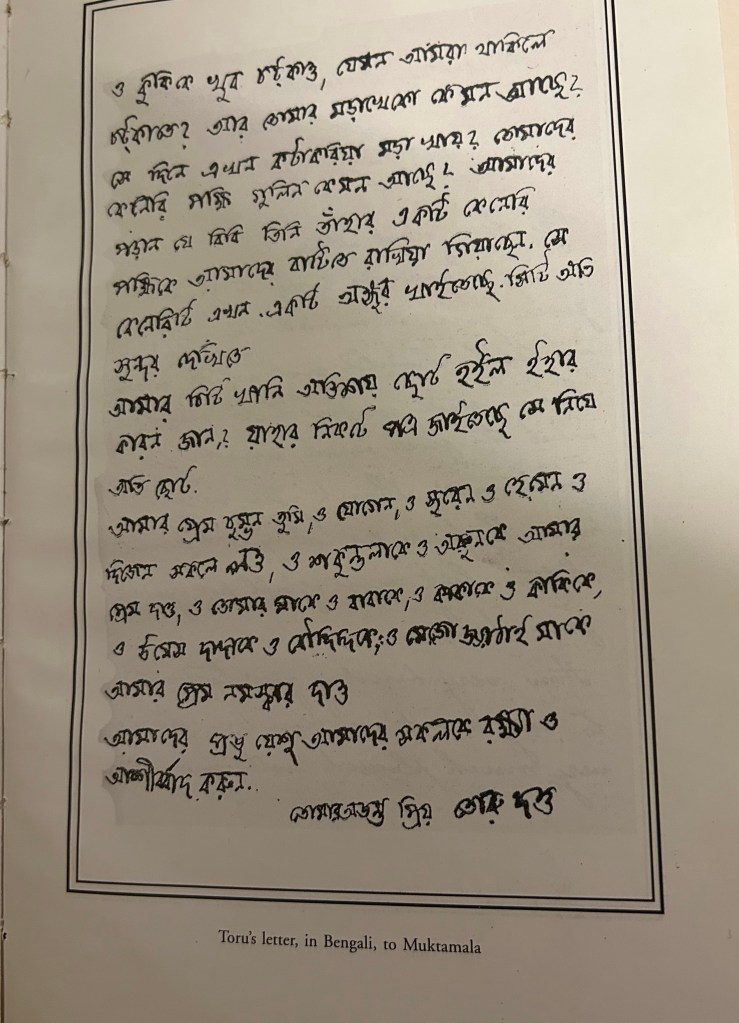

Tom Raw , The Griffin, A Burlesque Poem, London 1828,

Calcutta Through British Eyes, Laura Sykes, OUP 1992.

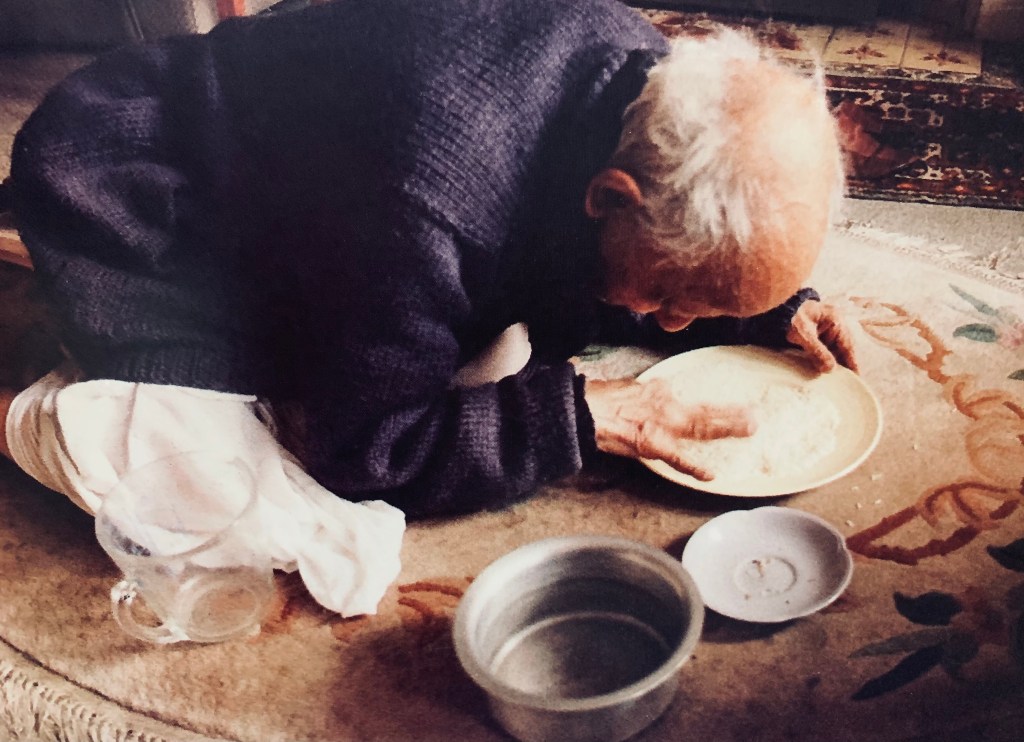

The photographs were taken by the author at Bath in September 2025 who, in her search for Sally Lunn Buns, had to weave through a maze of shops selling Austen samosas and Thai curries.